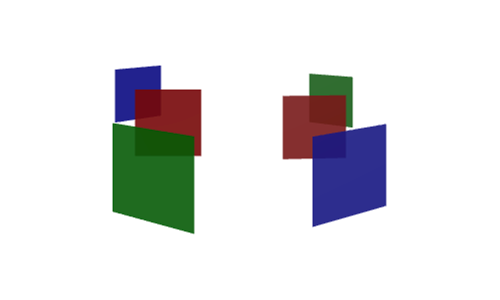

Transparency — or more precisely, translucency — remains a problem when rendering in 3D. When you have translucent shapes, the order in which they get rendered is very important. Consider what happens if this is done incorrectly.

Today, getting the correct order for translucent faces typically involves sorting the faces by their distance to the camera on the CPU, then sending the sorted faces to the GPU. This means every time the camera moves, you need to re-sort the translucent faces.

In this post, I will show a method I believe may be unique to sort faces independently of the camera position. This sorting is more expensive — O(n²) compared to O(n log n) — but it only needs to be done once. As this sorting is more expensive, it is only really suitable to places where the translucent faces do not move much. There are also some cases where it won’t work, and will have to fall back to CPU sorting.

We don’t need to know too much about GPUs for this post, but you do need to know GPUs will do anything other than sort geometry.

For opaque faces, you can imagine the GPU takes an array of faces, and each face is drawn one-by-one, in the order. To make sure faces farther away from the camera don’t start drawing over faces closer to the camera, they keep a per-pixel record of the closest distance rendered from the camera. Then when drawing each pixel in a new face, they’ll only draw it if it’s actually closer to the camera. This means they can avoid sorting the geometry, for opaque faces at least.

There’s one more thing about GPUs you’ll need to know to understand this post, which is face culling. This is an optimisation available to reduce the number of faces you have to consider. If you imagine each face like a coin, with heads and tails, face culling is a way to say only draw faces if you see ‘heads’ on the face. Typical use for this is when rendering volumes. First, you would set up a cube where the faces on the outside are all heads. Now when rendering, the faces at the back would show tails. The GPU can very quickly discard these faces — it doesn’t even need to do the depth testing we described before.

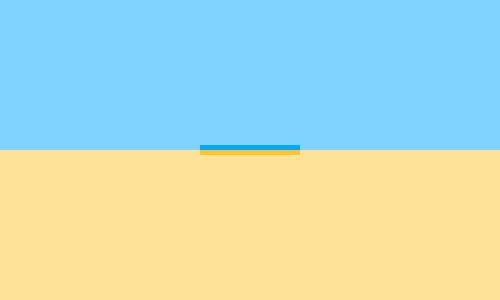

Face culling may seem like an odd thing to use for translucent faces — after all, you need to see the face from whichever way you look at it. However, if you split the face into two sides, and the two sides are flipped opposite to each other, you will always see one of the sides regardless of your camera position. Importantly, this means we can sort the two sides of this face into two different positions in an array.

Above, we show a single face split into two. In the blue section, you’ll see the blue side of the face; and in the yellow section, you’ll see the yellow side of the face. Notice there is no point where you can see both sides at once.

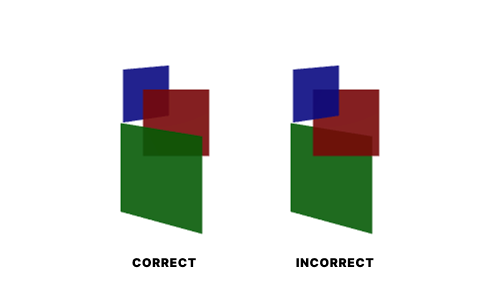

Now, we’ll look at what camera perspectives are available when we add another face. To simplify the example, we’ll only look at one side of each face at a time, and in two dimensions.

In this example, we can see the green and red areas overlap in exactly one area.

The grey-dotted area corresponds to a camera position where you could see an overlap of the faces. In the left half, looking at these two faces would show both green and red. In the middle section, it’s not possible to see two faces. In the right section, neither face is visible, so you won’t see an overlap.

Considering the areas where you can see both sides of the faces and where you could see an overlap, you can safely say for this example, you can always render green on-top of red.

Now we’ll look at the other permutations of each side of these faces.

This is the exact opposite of the case above. The red and green areas are flipped. With this face-side combination, you can always render red on-top of green. Remember that because these are different sides of the face, they can be sorted differently — so this doesn’t contradict the previous example.

In this case, it’s not possible to see both faces at the same time — sorting order is unimportant.

Here, you can see both faces at the same time. However, they won’t overlap at any point. Again, the sorting order is unimportant.

Consider a pair of faces, A and B. Consider the plane A is on, and all the vertices (‘corners’) from B. The vertices from B will either be wholly above the plane, wholly below, a mix of above and below (intersecting), or exactly on the plane (coplanar).

For the coplanar case, you can ignore the sorting order, as the faces won’t be able to overlap from any camera perspective.

If the vertices from B are wholly above the plane of A, your first instinct may be A must be rendered before B (farthest away faces get rendered first).

We actually have to look the reverse case too — if you flip the arguments.

In this case, green is wholly above red, and red is also wholly above green. As you can only see at most once face at a time, the sort order does not matter.

Only if B is wholly above A, and A is wholly below B can you guarantee A is rendered before B.

Now consider a case where the faces intersect. It’s still possible to have one of the faces be wholly above or below.

From this example, you can see that even though red intersects green, red is wholly above green.

Below is a table showing face configurations and their corresponding sort order.

| A→B (A’s vertices against B’s plane) | ||||

| ↑ Above | ↕ Intersecting | ↓ Below | ||

| B→A | ↑ | *1 | AB |

AB |

| ↕ | BA |

*2 | AB | |

| ↓ | BA |

BA |

*1 | |

You’ll note because it’s possible to have no sort order for some pairs, there is no overall sorting order — just constraints on some pairs. This means to sort, you have to check every face against every other face — O(n²).

Lastly, if you have to fall back to CPU sorting, it should be possible to only dynamically sort the groups that contain double intersections, and leave the rest pre-sorted. You will, however, have to track groups that need dynamically sorting — which I won’t cover.

I’ve written a quick implementation of this with Three, which you can open on StackBlitz. Note this example only handles rotating faces about the Y-axis. This is just for simplicity’s sake rather than being a limitation.

Pan around using the arrow keys — or if you’re on mobile, you can just look at the screenshot below showing a few faces from two opposite-facing camera perspectives.